The most precious of essences have long been associated with kings and queens. Courts have been seeped in scent for centuries, but perhaps the most aromatic aristocracy was to be found in the sultan’s court of Deccan era of India from 15-1700’s and the “Perfumed Court” of Marie Antoinette and Louis XV1 in the late 1700’s. Both courts regaled in the sumptuousness of scented places and gardens, and the decadence of rare and beautifully composed perfumes.

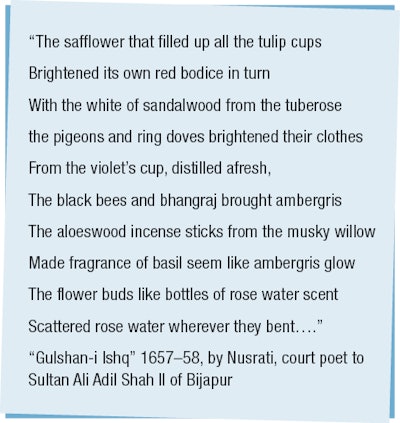

In the palaces of Sultan Ali Adil Shah II of Bijapur, scent reigned supreme. Both poetry and painting of the time spun aromatic tales full of flowers, mythology, romance and longing.

Poetry was linked with the planting of aromatic gardens, informing placement of flowers, plants and trees.

There is the tale of the Parijata flower, so auspicious, it was the only flower plucked directly from the ground and handed in offering to the Gods. Pa-rija-ta was a mortal princess who fell in love with the Surya, the sun god who rode his fire chariot across the sky from East to West. After a tryst on earth, and with the coming of summer, his divine heat became too strong, and he deserted her as night descended. Devastated, Pa-rija-ta followed the sun god and was burned by his heat. The Gods took pity on the lovers, and Pa-rija-ta was reincarnated as a night blooming jasmine tree, which Surya visited each day, his kisses causing the lingering fragrance.

Unable to stand the sight of the lover who left her, the Pa-rija-ta flowers only at night, shedding fragrant blossoms in the shape of teardrops. 1

Mentions of sweet smelling flowers in Deccan poetry and mythology often allude to sensuality and arousal. Outdoor pavilion gardens were set along streams. The flowers were placed with great care next to one another for their mingling of scents; both in the daytime heat and coolness of night. A canopy of coconut trees and surrounding cypress would provide shade from the burning sun, and the dry scent of hot clay and cooler notes of khus, or wild vetiver, were placed down as mats, and would release a cooling green aroma with every footfall. Basins of rosewater were set at the foot of flowering trees, so as to lure the flowers into fuller blossoms. The climbing trellises of aromatic hundred-petaled rose, violet, hundred-petaled marigolds, champa flowers, and strident notes of pomegranate, orange, fig and mango, would shine in the daytime. The aroma would linger in the evening hours when the gardens were set alight with burning aloeswood, frankincense, sandalwood, and fragrant ambergris candles. In the moonlit garden, one would find the heady, intoxicating scents of moonflower, night blooming jasmine, and tuberose, the queen of flowers. The garden, sliver-lit and artfully aromatic, was one of sensuality, seduction, and poetry.

“With its brimming cups and goblets, the candles aglow in its line of trees, this garden of light and perfume is the garden of the heart and the heart’s lamp and bud, kindled by the rosewater of heavenly dew and the sweet breath of Love.” 2

There is tale of the Indian god of love, Kamadeva. He was armed with a bow of sugar cane, its string a line of bees. The five arrows were tipped with blossoms to pierce the heart through five senses, his favorite arrow being the mango flower. 3

“The use of fragrances to charge a space with pleasure and assist induction of the appropriate mood may be among the ancient secular uses of perfume. The Itr-i Nawras Shahi describes nine methods for perfuming the royal bedroom...made up of the significant nine flavors, while a wholly new flavor by itself.” 4

The sultan’s bedchambers would lead directly off of the garden, the room an orchestra of deep, full flowers, animalic musks, spices and succulent, sweet fruits. Equal amounts of agar, saffron, musk, aloeswood and ambergris would be crushed and strewn about the room over the vetiver floor mats. Aloeswood incense and ambergris candles would burn within the chamber, and garlands of fresh jasmine, rose, marigold and champa flower would adorn the ceiling and walls. Vetiver blinds would cover the windows, releasing the cool green scent with each breeze. Silver and glass bowls of flowers and fruits were set by the bed and composed with the care of bouquets: citron at the bottom, overlaid with jasmine blossoms, topped with layers of roses and champa flowers, and then sprinkled with rose water. When the incense was lit, the bedsheets would be lifted above the aromatic smoke, so as to capture the fragrance in the material. The effect would be “enticing, invigorating and pleasure giving.”5

The sultan, was seen as divine, and as such, enjoyed a bathing ritual enwrapped in mythology and meaning; the perfect balance of aromas speaking of perfection within.

He would be bathed in violet and rose water, then rubbed with fragrant sandalwood and rosewater paste, which was beautifully scented and cooling to the skin. Sandalwood powder would be combed through his hair, and he would chew on peels of fruit and scented wood to keep his royal breath fresh while having perfumed paste applied to his body. The Sultan’s clothing would be dyed with aromatic woods and brick ash, and then perfumed by lifting them over burning agarwood.

In 1469, a sultan named Ghiyath Shahi wrote the Book of Delights, a rather detailed recipe book instructing the use of herbs, flowers, woods and resins in both perfume and food preparation. Many chapters focus on perfumes for the "House of Pleasure," the moniker for the royal harem. One recipe details the preparation of Abir, a complex and gorgeously perfumed paste for the body which contained “…mango, ambergris, beans, marhatti herb, similar to anise, aloes, perfumed fat, bruised grain, chauva, (a paste of sandal, agarwood, saffron, and musk), essence of mouse-ear plant, Chinese camphor, boiled juice of spikenard; put in flowers scented with aloes, white sandal essence, scent from shoots, sesame oil scent, sweet basil essence, champa essence, artemisia essence, turmeric leaves essence, sacred basil essence, cardamom juice, and sandal juice.” 6

Really raising the bar of the proverbial beauty ritual and putting our modern spas to shame, in yet another recipe the sultan offers advice for scenting a woman’s body, proving his devotion to aromatic sensuality.1 “Rub perfume separately into each joint. (Use) pellets of perfumed paste. Wash hands in rose water. Take the sap from the bark of the mango tree and from the bark of the wild fig tree, and from peepal tree and wash the body with it. Rub aromatic paste, perfume and musk into the armpits. Rub rosewater and musk onto private parts and rub sandal on the throat. Essence of musk is good for the mouth, also put aloes perfume into the mouth.” 7

The sultan ’s suggested pampering included dabbing her forehead with rosewater, anointing oils of every kind on her body, and sprinkling her head with spikenard while she sniffs fresh flowers. Then, her face should be rubbed with saffron, and teeth polished with jasmine powder. Her body would be once again rubbed with fragrant oils, then doused in rosewater with twigs, and a final wash in cold water.

Fragrance seeped into every moment of life at the court, and was considered as important to health as pleasure. One’s inhalation must be filled with the balance of aromas that would provide both cooling and heating humors within the body, and thus scent was seen as an integral part of the balance of the internal spirit.

The palatial gardens and bedchamber were a perfectly composed aromatic and visual experience. One note would lift on the breeze, another would follow in a song of fragrance and play of color. Flowers, woods and herbs would be intricately positioned to ingeniously mock the aroma of certain heady, single animal notes like musk or civet, ambergris and alsoeswood. Delicate pinks, bright yellows, greens, furious reds and deep browns created a patchwork of hues illustrated in the many paintings of the era. The greenery, incense, candles and fresh flowers became the manifestation of a perfume: one living, breathing, immersive scent. Note by note, the fragrances filled the imagination, inspiring the senses; resonating chords of fragrance speaking of sophisticated artistry and a devotion to the pleasures of a perfumed life.