Product research traditionally assesses cognitive, or System 2: reactions to stimuli to guide product development. To diagnose what is well liked and why, traditional cognitive consumer product research typically utilizes Likert scales, or check-all-that-apply attribute lists to score different products. The consumer responds to how they feel about the product with time allowed to construct and rationalize their opinions.

Some research disciplines have advanced beyond cognitive methods to measure System 1: subconscious reactions. Studying the subconscious allows researchers to understand consumers’ emotions that influence their behavior and experience, yet cannot verbalize. Applied consumer neuroscience is a growing field which measures the subconscious via physiological responses. For example, the field of advertising research has been an early adopter of applied consumer neuroscience. In advertising, it has been used to identify such things as effectiveness (emotional engagement), impact of branding moments, and to specify areas of ads that need improvement. Applied consumer neuroscience reports have been used to optimize communications in TV advertisements, print ads, messaging, branding, social media and website UX. Here it has become an increasingly popular tool for measuring engagement with communications and for providing data points to deliver relevant advertising experiences.

When consumers experience a product, they do so 5-dimensionally via the five sensory systems: taste, touch, sound, sight and smell. Each of these senses becomes an opportunity for communication of a product’s concept, branding and even higher-order benefits (such as stress relief, moisturization, etc.). These sensory communications become part of the overall product and brand messaging as well. Therefore, it is important to assure there is alignment of product sensory attributes with brand and product concepts to ensure a positive and cohesive product experience. For example, the emotional qualities of the fragrance should be aligned with the emotional communications of the package, the brand and the advertising. When these pieces are not cohesive, it can contribute to consumer dissatisfaction and negatively impact consumer liking.

The need for understanding the emotional responses in sensory and consumer studies has become more and more frequent and necessary in the last ten years.

The introduction of applied consumer neuroscience in consumer product research is a relatively new yet rapidly growing field. Q Research Solutions (Q) set out to examine the value of incorporating neuroscientific measurements in consumer product research. If we can measure the system 1 responses of subconscious reactions, could there be valuable additional insights? How could going beyond measuring pleasure, or hedonics, to understand experiences—which are not verbalized by consumers—help guide product development?

To investigate, Q conducted a study employing applied consumer neuroscience, working with HCD’s HedonicsPlusa methodology to see if and how neuro-physiological testing would result in enhanced emotional profiles, an improved understanding of consumer preferences and subsequently provide better guidance for product development.

Materials and Methods

Q & HCD chose to conduct the study with the four different tropical plug-in scented air fresheners, chosen because it is a lead olfactive direction within a well-developed category. The consumers who participated in the test were female, aged 18 – 60, who had purchased tropical or exotic fruits plug-in scented oil air fresheners in the past six months. The panellists were tested for both cognitive and subconscious responses to the four different products—identified here as Product A, Product B, Product C and Product D.

Test protocol and samples

The consumers tried the four products in a sequential monadic two-stage study over two days. The studies were carried out following ASTM protocol, using eight identical air flow controlled booths which use positive airflow to eliminate cross contamination. In the first stage, consumers entered a pre-fragranced booth and provided ratings on liking, fragrance intensity and other explicit measures.

In the second stage, neuro-physiological procedures involved measuring physiological responses from electrodes placed on the consumers’ face (facial EMG), hand (Galvanic Skin Response) and wrist (heart rate variability)

They entered the fragranced booth while wearing nose clips in order to avoid fragrance exposure until prompted; once seated they were instructed to remove the nose clip to start the test. Consumers were asked to sit and breathe normally for 15 seconds while physiological responses to fragrance exposure were captured. They then moved on to the next fragrance booth and repeated these steps.

Ratings

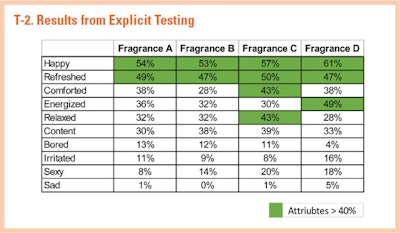

In the traditional explicit stage, 10 attributes – happy, contented, comforted, refreshed, sex, energized, irritated, relaxed, sad and boring – were assessed via a check-all-that-apply list. These were selected to cover positive and negative valence as well as high and low arousal.

Check-all-that-apply data was analyzed using a simple frequency table so that we can see the percent of consumers who selected each attribute per fragrance. The higher the percent of consumers who selected an attribute, the better that attribute described the fragrance. Hedonic and intensity measures were analyzed using an Analysis of Variance with a Fisher LSD Post Hoc test.

Results of the Explicit and Neuro-physiological Testing

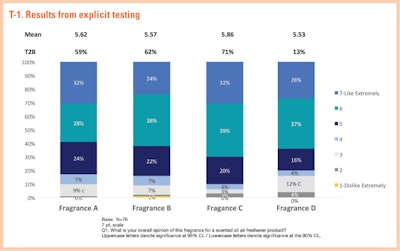

All of the fragrances tested scored parity for overall liking, a familiar problem within product testing (T-1).

Therefore, product development guidance would need to come from other measures. The emotional profiles from the explicit measures yielded key insights. Namely most of the products were rated as happy and refreshed by the consumers (T-2).

We found that by layering on applied consumer neuroscientific measures, we uncovered additional understanding of emotional resonance. Positive emotion was not as clear from the biometrics, for instance. Three of the four fragrance profiles included negative valence with attributes such as irritation, annoyance and negative arousal. Further, it revealed how the emotional reactions changed over the time course of fragrance exposure. In the case of one fragrance, we were able to measure how the response which was initially neutral became more approachable or welcoming towards the end of the experience.

For Product A, the experience, as revealed by the neuroscientific approach, was fairly neutral – even boring. There was a positive valence at the beginning which began to significantly decrease over the period of exposure. The testing of Product A also showed a moment of significantly decreased negative valence.

With Product B, there was a decrease in positive valence immediately, followed by a decrease in negative valence. In other words, this fragrance was arousing, but not immediately. The responses indicated some disengagement with the fragrance with a combination of increased arousal and decreased attention.

Product C was found to be arousing up front and for most of the experience. This was negative as well as positive, however, resulting in a tension between the two responses. At the same time the consumers found this fragrance to be less approachable, suggesting some distraction or disengagement.

Product D had an overall negative valence reaction and the arousal was sustained for half of the experience. The fragrance was initially aversive, becoming more approachable and welcoming over the period of exposure (F-1).

Conclusions

What does this all mean?

The fragrances we examined all scored well hedonically. In fact, they were parity for liking. This is a very common result in flavor and fragrance testing. A fragrance house is charged with making several options to choose from and, of course, they are able to offer really great, well-liked samples. Brand managers and product developers are then left to try to decide which is the best to move forward with.

When a consumer approaches a product on shelf, she may pop open the top to sniff it. Does she like it? Probably, it was a well-designed fragrance. But is that enough to drive purchase? The product experience is more than just a hedonic experience, there is also an emotional and functional experience which must be considered. Which is why in addition to understanding how much consumers like a product, we also need to assess attributes such as comforted, energized, refreshed, happy etc. to understand if the product will meet all the needs of the consumer beyond liking.

Seeing how the fragrance changed consumer perception over time based off of physiological measures has allowed us to better understand the consumer experience. For example, Fragrance D evolved over time, becoming more approachable, signaling that this product would perform well over longer exposures in an in-use environment. While first impressions are very important to the consumer, understanding how perception and experience changes over time allows us to differentiate similar test samples in ways that traditional research cannot. These nuances can reveal large differences between samples, differences in experience that consumers may not even be aware of or able to articulate, but that influence their overall perception of the product.

This novel holistic approach to consumer science will provide product developers and consumer scientists with a sensitive and efficient way to better understand consumer behavior and emotion, differentiate changes to product attributes and make more informed product design decisions.