*Editor's Note: This article has been edited on February 23, 2018 to clarify the relationship between the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM), the Expert Panel and the International Fragrance Association (IFRA). The author refers to RIFM as the "scientific arm of IFRA." This is incorrect. RIFM operates independently as an international safety authority for the safe use of fragrance materials.

RIFM is not an arm of IFRA, but rather a separate organization that works in conjunction with IFRA through the expert panel for fragrance safety. Additionally, the Expert Panel is not a part of RIFM, rather it operates independently from the two organizations and is comprised of a panel of experts that review the activities of RIFM, official agencies and the industry.

To maintain RIFM's unbiased scientific support for the safe use of fragrance materials, these three organizations must remain independent. RIFM, the Expert Panel and IFRA have always acted as separate and independent entities.

We regret the error.

With consumer safety at the forefront of product development, EU and global regulations facing fragrances in cosmetics can offer robust and dynamic research methods for an evolving label.

IFRA and RIFM – Voluntary Measures

The International Fragrance Association (IFRA) represents the interests of the fragrance industry with the main purpose of promoting the safe use of fragrances worldwide.1 The Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM) is an independent, international safety authority for the safe use of fragrance materials. The expert panel for fragrance safety also operates independently to review the activities of RIFM, official agencies and the industry. All three organizations work independently to promote fragrance material safety.

The IFRA Code of Practice includes scientifically-based recommendations (usage standards) which are intended to ensure the safe use of fragrance materials in products. The expert panel for fragrance safety, which consists of dermatologists, pathologists, toxicologists and environmental scientists, is completely independent of the fragrance industry and assesses the available scientific data on fragrance ingredients. The Expert Panel evaluations are used by IFRA to develop their Code of Practice Standards on fragrance material usage.

The Code of Practice is adopted by IFRA member companies worldwide, and affects the manufacture and handling of all fragrance materials, for all types of applications, including cosmetics and toiletry products. Although IFRA membership is voluntary and the Code of Practice is not legally binding, adherence is mandatory for IFRA members. According to IFRA figures, its member companies currently supply 90% of the global fragrance market. Most cosmetic product manufacturers expect their fragrances to comply with IFRA standards.

The IFRA Code of Practice is regularly amended to include new or revised usage restrictions. The most recent (48th) amendment was published in 2015 and it is expected that the 49th amendment will be published in the second quarter of 2018. Following the publication of an amendment, there is usually a period of adaption before full compliance is required, to allow industry to implement the changes.

The EU Cosmetics Regulation – Legally Binding Measures

As membership to IFRA is not compulsory, not all fragrance houses follow its recommendations. Nevertheless, this does not imply that non-IFRA compliant fragrances are unsafe for use in cosmetics.

Any cosmetic product placed in the EU market must comply with the provisions of EU Regulation 1223/2009 (the Cosmetics Regulation),2 and this also includes ingredients used in fragrances. Any fragrance house wishing to commercialize their products in the EU must therefore comply with the cosmetics regulation, regardless of their IFRA affiliation status. In contrast to the IFRA Code of Practice, the Cosmetics Regulation is legally binding. Therefore, in the case of discrepancy between the IFRA Code of Practice and the provisions of the Cosmetics Regulation, the latter must be applied in the EU.

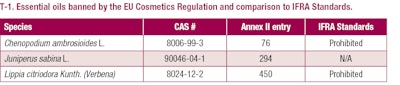

According to the Cosmetics Regulation, some fragrance ingredients are banned. Entries 423 to 450 and 1133 to 1136 in Annex II of the Cosmetics Regulation list these substances, which include alanroot oil (Inula heleniumL.), fig leaf absolute (Ficus caricaL.), and costus root oil (Saussurea lappa Clarke) among others. All of these ingredients are also prohibited under the IFRA Code of Practice. Annex II of the Cosmetics Regulation also bans three essential oils, of which two are also prohibited by the IFRA Code of Practice (see T-1).

In addition to the banned substances listed in Annex II, Annex III of the Cosmetics Regulation includes restrictions on the use of some fragrance ingredients. According to the Regulation, 26 fragrance allergens (entries 45, 67 and 69 to 92a) must be declared on a cosmetic product’s label ingredient list if these are present at concentrations above 0.001% (for leave-on products) or 0.01% (for products that are rinsed off). The aim of this requirement is to ensure that sensitive (i.e. allergic) consumers are informed of the presence of allergens in the cosmetic product. Nevertheless, the final concentration of these fragrance allergens in the finished product is not restricted by the Cosmetics Regulation. In contrast, the IFRA Code of Practice establishes concentration limits in the finished product for these allergens, except for linalool and limonene, for which only specification standards are stated (i.e. peroxide levels should be kept to the lowest practical level); interestingly, the Cosmetics Regulation does restrict the peroxide values for limonene to below 20 mmoles/L for the pure substance.

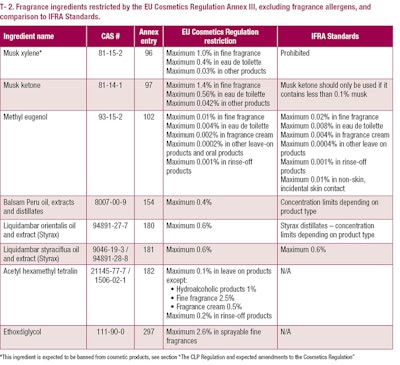

Other ingredients restricted by Annex III of the Cosmetics Regulation are listed in T-2. As stated in the table, restrictions required by the Cosmetics Regulation are not always in line with the IFRA Code of Practice.

Recent Amendments to the Cosmetics Regulation

In common with the IFRA Code of Practice, the provisions of the Cosmetics Regulation regarding fragrance ingredients are scientifically supported.

Proposals for the inclusion of ingredients in the Regulation’s annexes may come either from industry or from National Competent Authorities. A dossier with data on the ingredient is submitted to the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS), who reviews the information provided and issues an opinion on the safety of the ingredient.3 Based on this scientific opinion, the European Commission drafts an official proposal for adaptation to the Annexes of the Regulation. The Standing Committee on Cosmetic Products (COSCOM) discusses and votes on the proposal. If the proposal is accepted, a formal amendment to the regulation is issued and published in the Official Journal of the European Union (OJ), meaning that the regulation has been officially amended, including bans or restrictions on an ingredient.

Following this procedure, three fragrance allergens were banned from use in cosmetic products in August 2017.4 The SCCS had previously concluded in its 2011 opinion5 that hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde (HICC or lyral), 2,6-dihydroxy-4-methyl-benzaldehyde (atranol) and 3-chloro-2,6-dihydroxy-4-methyl-benzaldehyde (chloroatranol) should not be used in cosmetic products as these are the fragrance allergens which appear to be responsible for the highest number of cases of contact allergy. As a consequence, these allergens were included in Annex II of the Cosmetics Regulation (banned ingredients), and entry 79 of Annex III (which permitted the restricted use of HICC) was deleted. In order to provide a reasonable period of time for industry to adapt to these changes, the ban on the placing on the market will effectively apply from 23 August 2019, and 23 August 2021 will be the deadline for the withdrawal of any cosmetic product containing these ingredients.

It should be noted that atranol and chloroatranol are natural components of oak moss (Evernia prunastri) and treemoss (Evernia furfuracea) extracts, which are separately regulated by entries 91 and 92 of Annex III of the Cosmetics Regulation, respectively. The IFRA Code of Practice currently restricts the concentration of HICC (different concentrations depending on the product type) and limits the levels of atranol and chloroatranol below 100 ppm in oak moss and treemoss extracts; however, these restrictions are not in line anymore with the provisions of the EU Cosmetics Regulation.

Expected Amendments to the Cosmetics Regulation

The Scientific Committee on Consumer Products (SCCP), the predecessor of the SCCS, concluded in its 2005 opinion6 that Tagetes erecta, Tagetesminuta and Tagetes patula extracts and oils, which are widely used fragrance ingredients, should not be used in cosmetic products as no safe limits had been demonstrated. The SCCS revised the opinion in 2015 after a dossier update7, and concluded that for Tagetes minuta and Tagetes patula extracts and oils in leave-on products (except sunscreen products), a maximum concentration of 0.01% is safe, provided the alpha terthienyl (terthiopene) content in the extracts and oils does not exceed 0.35%.

The SCCS also concluded that these ingredients should not be used in sunscreen products. In a later comment to the opinion, the SCCS also stated that a 0.1% should be established as the maximum concentration for these ingredients in rinse-off products. A draft commission regulation implementing the SCCS recommendations was published in July 2017. This draft bans Tagetes erecta, restricts the use of Tagetes patula and Tagetes minuta (including purity specifications regarding terthiopene), and bans the use of Tagetes patula and Tagetes minuta in sunscreen products. The deadline for comments was 10 September 2017. The proposed date for adoption is the fourth quarter of 2017 and 9-month and 12-month adaptation periods are expected for placing on and withdrawal from the market, respectively.

Fragrance Ingredients under SCCS Assessment

As stated above, amendments to the Cosmetics Regulation are based, to a great extent, on the opinions of the SCCS. The SCCS has recently reviewed or is currently considering several issues which concern the fragrance industry.

In the same opinion of 2011 that led to the banning of three allergens in cosmetic products5 (see above), the SCCS also identified 129 fragrance ingredients which have been shown to be sensitizers in humans (including the already regulated 26 allergens). Of these, 82 were classified as established contact allergens in humans, 24 were categorized as established contact allergens in animals, and 23 were considered likely contact allergens by a combination of evidence.

The SCCS was of the opinion that the consumer should be made aware of the presence of these substances in cosmetic products, meaning the list of allergens to include on the product label would increase from the current 26 allergens to a minimum of 82 substances (established contact allergens), and potentially up to 129 ingredients if all of them were to be considered. A public consultation on this proposal was launched by the European Commission in February 2014 (closed in May 2014), but up to date, no legal changes have been implemented.

The technical difficulties and economic implications of this proposal have slowed down a regulatory process that was initially expected to be completed by the beginning of 2015. As an example of the concerns raised by the industry, IFRA responded to the consultation by addressing two issues.8 Firstly, a concern was raised over the need to develop new analytical methods to determine the concentration of the newly identified fragrance allergens. In November 2016, this was successfully addressed, when IFRA released the protocol for the analytical method to quantify 57 suspected allergens (and isomers) in fragrance materials.9

Secondly, IFRA was of the opinion that substance labelling “has not helped protect people already sensitized from elicitation while often confusing the vast majority of the other un-sensitized population,” and that this situation would be “even more relevant when extending the list of allergens.” IFRA’s proposals to address correct delivery of information to the consumer included the use of pictograms, pack warnings, web-based sources and free access to consumer help desks. Up to the present, no consensus has been reached on the most appropriate approach to inform the allergic consumer.

As a final comment on the same SCCS opinion of 20115, it also suggested that 12 single chemicals and eight natural extracts should be subject to concentration limits in cosmetic products. As further scientific work is needed to determine these concentration limits, no regulatory action has been undertaken so far.

Other Fragrance-Related Topics

In October 2016, the European Commission submitted a third request for an opinion on acetylated vetiver oil. The first request was submitted in 2005 by the European Flavor & Fragrance Association (EFFA) to the SCCP, who released an opinion in 200610 stating that the information submitted was “inadequate to assess the safe use of the substance.” A second request was submitted by IFRA in 2013. After the corresponding SCCS opinion was released in 2014,11 and during the commenting period, IFRA raised the necessity to modify the initial request. IFRA recommended several safe concentration limits for acetylated vetiver depending on the cosmetic product category in which the ingredient is intended to be used. The current (third) submission requests the SCCS opinion on the safety of acetylated vetiver oil as a fragrance ingredient in cosmetic leave-on and rinse-off products at the concentration limits established by IFRA. The initial deadline for this opinion was March 2017, but a request for clarification was sent to the applicant and the publication of the final opinion has been delayed.

Butylphenyl methylpropional (BMHCA, lilial or lysmeral) is one of the fragrance allergens listed in Annex III of the Cosmetics Regulation (entry 83, see above). This ingredient is regulated for labelling purposes but has no concentration restrictions. Nevertheless, the IFRA Code of Practice establishes concentration limitations depending on the product type. In 2013, a public consultation was launched to address the possible classification of the ingredient as a reprotoxic compound according to the CLP Regulation. In response, IFRA requested the SCCS opinion on the ingredient. The SCCS opinion,12 published in 2015 and revised in 2016, concluded that BMHCA is not safe for use as a fragrance ingredient in leave-on and rinse-off type cosmetic products at the concentration limits established by IFRA. The SCCS could not draw a firm conclusion on the mutagenicity of BMHCA, and expressed its concern that the ingredient poses a risk of inducing skin sensitization in humans.

In June 2017, a second opinion on BMHCA was requested to the SCCS, after IFRA submitted a new dossier containing additional data. The new dossier clearly distinguishes between the para and meta isomers of the ingredients, defending the use of para-BMHCA. It also includes a revised proposal for maximum use levels of p-BMHCA in different cosmetic product types. The deadline for the publication of the draft opinion is December 2017. It is important to note that an official classification proposal for BMHCA as a Category 2 reprotoxic substance under the CLP Regulation was submitted in May 2017. If the ingredient is finally included in Annex VI of the CLP Regulation (a process with a timeline of about 2 years) and no positive opinion is delivered by the SCCS, BMHCA would be effectively banned from use in cosmetic products in the EU.

In 2006 IFRA published and implemented a dossier describing the Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA) methodology.13 The QRA methodology aims to assess the sensitization risk of fragrance ingredients, that is, to establish concentration limits below which these ingredients do not pose a danger for consumers. The use of QRA for fragrance ingredients should facilitate the establishment of IFRA Standards. Despite the QRA representing an important step forward in skin sensitization risk assessment, it was recognized that further refinement to the method was needed. In fact, the SCCP reviewed the method in 2008 and concluded that “the model has not been validated and no strategy of validation has been suggested.”14 They were of the opinion that there was no confidence the identified thresholds for skin sensitizers were safe for the consumer.

Some additional criticisms were, firstly, that the QRA model was based on data from sensitization tests in humans (e.g. Human Repeated Insult Patch Tests (HRIPT)), which does not have an in-depth method description and is considered to be unethical to perform. Secondly, epidemiological and experimental data providing information on sensitization/elicitation reactions in consumers by marketed products were not integrated in the QRA model.

The SCCP was of the opinion that safe levels of exposure to allergenic substances should be based on clinical data and/or elicitation low-effect levels. Nevertheless, the SCCP recognized that, after refinement and validation, models like the QRA could be applicable for risk assessment of new substances for which data is not available. They suggested aggregated exposures should be incorporated in the QRA model, as well as a validation employing a broad range of chemicals and clinical data. In their opinion of 20115 the SCCS reiterated this opinion. Following this evaluation, a new QRA methodology has been developed (and named QRA 2), which reviews uncertainty factors and introduces dermal aggregate exposure data. In March 2017, the SCCS was requested an opinion on the new methodology. The draft opinion is expected for October 2017, which is the deadline set up in the opinion request.

The CLP Regulation and Expected Amendments to the Cosmetics Regulation

Although it does not directly address cosmetics, the provisions of Regulation 1272/2008 (the CLP Regulation)15 do have an impact on these products. According to Article 15 of the Cosmetics Regulation, the use in cosmetic products of substances classified under Annex VI to the CLP Regulation as CMR (carcinogenic, mutagenic or reprotoxic) is prohibited.

Category 1A and 1B CMR substances (‘known’ or ‘assumed’ human CMRs) may still be used in cosmetics only if they comply with the EU food safety requirements16, there are no suitable alternative substances available, an application is made for a particular use of a product category with a known exposure and they have been evaluated and found to be safe by the SCCS for use in cosmetic products. Category 2 CMR substances (‘suspected’ human CMRs) may be used in cosmetic products if they have been evaluated by the SCCS and considered to be safe for use.

In July 2017, a draft Commission Regulation was published which explicitly prohibits or restricts the use in cosmetics of substances classified as CMR (in any category) according to the CLP Regulation as at 1 January 2017, by including them in Annex II or III of the Cosmetics Regulation. The deadline for comments on this draft Regulation was 28 August 2017. After this, the regulation is expected to be voted and published in the OJ by the end of 2017. There will be no adaptation period to the regulatory changes.

Some fragrance ingredients have been included in this draft regulation:

Furfural (2-furaldehyde), which is used as a fragrance ingredient in cosmetic products, is listed in Annex VI of the CLP Regulation as a CMR substance in Category 2. As the SCCS concluded in its opinion of 2012 that furfural is safe for use in cosmetics at concentrations of up to 0.001%,17 the ingredient will not be banned, but restricted. The draft regulation lists furfural in Annex III of the Cosmetics Regulation in order to restrict its use in line with the SCCS opinion. It should be noted that furfural is restricted by the IFRA Code of Practice to concentrations ranging between 0.001 and 0.05% depending on the product type. Nevertheless, changes to the Cosmetics Regulation are legally binding.

Musk xylene, which is currently listed in entry 96 of Annex III of the Cosmetics Regulation, is classified as a Category 2 carcinogen in Annex VI of the CLP Regulation. Although the last published scientific opinion, dated 2004, considered musk xylene is safe at the currently permitted concentration levels,18 as there has been no additional assessment by the SCCS regarding the safety of this ingredient in cosmetic products, musk xylene will be included in entry 1389 of Annex II of the Cosmetics Regulation and deleted from Annex III, and thus banned from use in cosmetic products. In line with this, musk xylene is prohibited in fragrances according to the IFRA Code of Practice, and its concentration limited below 0.1% in musk ketone preparations.

Conclusion

The safety of cosmetic products containing fragrances marketed in the EU is accomplished through the application of both voluntary and legally binding measures (the IFRA Code of Practice and the EU Cosmetics Regulation, respectively). Restrictions on the usage of fragrance ingredients stated in both texts do not always coincide, with the (legally binding) Cosmetics Regulation often being more restrictive than the IFRA Code of Practice. Therefore, following the IFRA recommendations, although intended to ensure product safety, does not fully guarantee regulatory compliance of a fragrance in the EU, as fragrance houses wishing to sell their products in the EU must also ensure full compliance with the provisions of the Cosmetics Regulation.