Being a perfumer in a smaller house means that your job description changes day-to-day, or even hour-by-hour. Perfumer Robert Siegel has dealt with it all—the last-minute projects, the distractions (raw materials sales calls) and customer cost concerns (shaving a few cents off the fragrance’s price). We recently spoke with Siegel about the stresses and strains of working for a small house and how perfumers can succeed under pressure.

P&Fnow: Can you briefly describe the kinds of ‘hats’ a small house perfumer is asked to wear?

Siegel: At a smaller perfume house, there is less “departmentalizing” of support staff. A perfumer does not always have a technician devoted to just his or her projects, as technicians may have to split their time compounding samples or running MSDS tests. Therefore, it can fall upon the perfumers to compound their own experiments, make up their own prototypes (applications), and prepare and evaluate their own analytical runs and interpretations. In addition, perfumers are often the “go-to” staff to answer sales personnel inquiries, customers’ technical questions, purchasing questions or preparing marketing descriptions.

P&Fnow: Keeping costs down is a high priority—especially when it comes to projects such as air care. How do you work around pricing limitations while still delivering the desired olfactory profile?

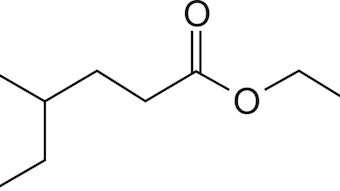

Siegel: Smaller perfume houses are often working with private label manufacturers who demand a match of national brand fragrances, but at a much lower cost. In addition, their base may be difficult to work with. Therefore, perfumers must be familiar with the vast array of aroma chemicals available, and seek out those that offer high impact at a relatively low cost. Some examples are rose oxide, “green” aromas such as cis-3-hexanol and iso cyclo citral, strong camphoraceous materials such as Verdol (IFF), certain aldehydes and butyrates, and cassis-type sulfur-based chemicals.

P&Fnow: You’ve written an article (Perfumer & Flavorist magazine, May 2007) in which you describe the last-minute formulation of an aloe vera baby wipe fragrance. Is this a typical experience? And have you learned any time-management tricks along the way?

Siegel: It would be rare that a perfumer only has one day to complete a fragrance submission, as is suggested in this article. But time is almost always a factor in some way, when juggling multiple projects and meeting deadlines. One way to save time is to make a 100–200 g sample of a fragrance “skeleton,” with all the major components included balanced to one’s liking. From this primary sample, many multiple smaller 10–20 g experiments can be created, adding various amounts of trace chemicals. This saves time from compounding the same sample over and over. Once an experiment is approved, the finished formula needs only to be made once more for customer submission.